I’ve been meaning to write a post about email newsletters that still assume you’re reading on a desktop and send out layouts that rely on a wide screen size and end up with tiny 2-point type on a mobile phone — you know, where most people read their email these days.

Then I stumbled on this usability article by Jakob Nielsen.

From 2012.

It pretty much covers what I would have said, and more. But a decade on, I still get email I can’t read without moving to a bigger screen.

The Time Before Tables

The funny thing is that HTML, by design, already adjusts to different sized displays, windows and terminals. In the very early days, you couldn’t make it not be responsive unless you added a block of pre-formatted text.

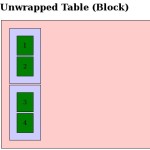

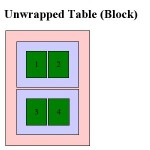

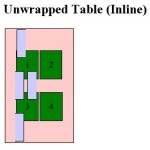

Once HTML picked up a little more rendering capability (tables, images and image maps), you had people designing websites who were accustomed to fixed-size media, and the paradigm stuck.

— Build your layout in Photoshop at 800×600, then slice it up into clickable pieces and reassemble the whole thing on a page!

— Wait, now we can aim for 1024×168!

— Oh, hey, we have widescreen now!

— Huh? What do you mean the window isn’t always fullscreen?

— Phones now? Ugh, I’ve gotta make a totally different website!

And so on.

Responsive Styling

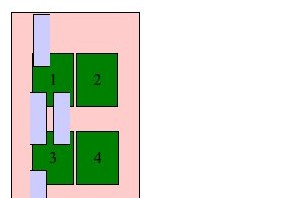

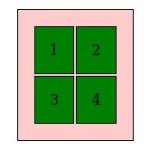

These days you can apply relative sizes to everything, and tweak the layout based on the logical screen size instead of physical pixels. (Shout-out to high-definition displays here!) Modern HTML+CSS is amazingly improved in flexibility, and if you plan it right, you can often just rearrange the same page for screens from small cell phone size up to those widescreen monitors. Obviously this depends on what kind of site or application you’re building.

But for email, especially for newsletters, where reading the text is the main point, it should be an obvious choice!

Expanded from this thread on Wandering.shop.