Google Photos has been sending me its usual “Rediscover this day!” collages from Comic-Con 2013. On Tuesday it sent me a collage built from July 18, and on Thursday it sent me a collage built from July 20, marking Thursday and Saturday of the event.

Wait, what about Friday?

Well, here’s the interesting thing: Friday was the day I spent the afternoon in the emergency room.

I’d like to think someone programmed the algorithm to skip photos tagged for hospitals. Imagine if it was my wife’s photo collection, and I hadn’t made it — “Rediscover this day” would have been rather cruel in that case.

The more likely explanation is that I don’t have very many photos from that day for it to pick from, at least not on the account. On my computer I have 19 photos from my phone, 19 from my camera, and 5 from Katie’s phone. Of those, I picked 21 for my Flickr album. In Google Photos, I only have six from that day, all from my phone — and they don’t include the ER wristband shot.

My best guess is that I cleared most of them from my phone sometime before I started using the cloud backup feature… but I can’t figure out why I would have kept the photos that are there, and not some of the photos that aren’t.

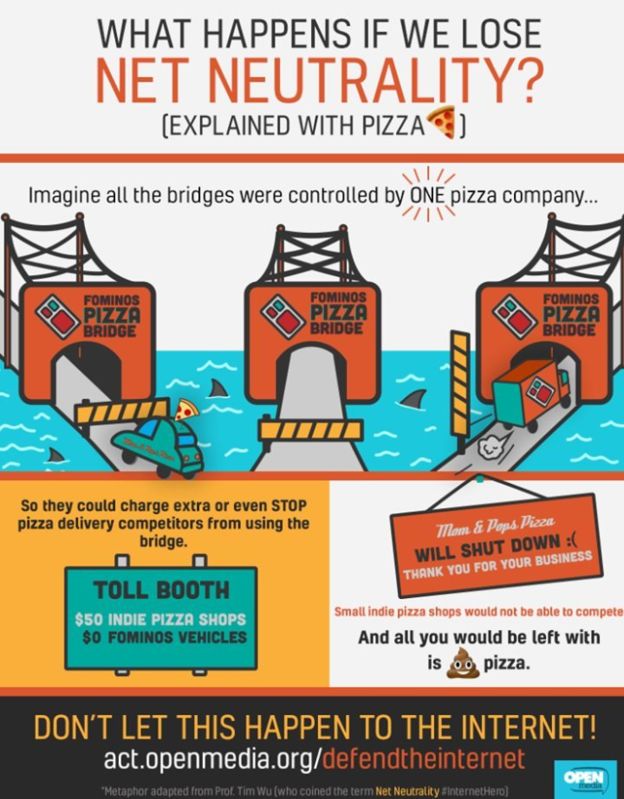

Here are the photos that are on there:

It’s an odd collection, isn’t it? The three individual frames from the GoT protester collage are in there, so maybe the collage app saved extra copies of the sources, and Photos found the folder. I can see deliberately keeping the view of the blimp from the convention floor (literally the floor), but if I’d done that, I don’t know why I wouldn’t have saved the wristband shot as well. And why save the Duplo Enterprise, but not the photos of my son playing at the LEGO booth?

Phone cameras and cloud storage are supposed to augment our memory. But sometimes the context is just missing.